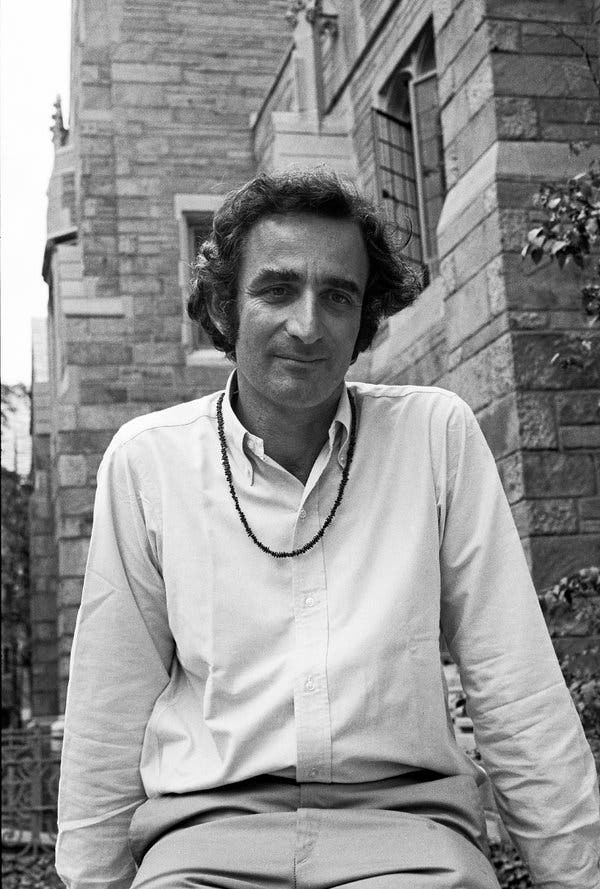

Charles Reich dead at 91

from nytimes.com

Charles Reich, Who Saw ‘The Greening of America,’ Dies at 91

By Sam Roberts | Jun. 17th, 2019

Credit Israel Shenker

Charles A. Reich, who as a 42-year-old Yale Law School professor swapped button-down Brooks Brothers shirts for hippie beads and vaulted to intellectual celebrity by venerating the counterculture in his manifesto, “The Greening of America,” died on Saturday in San Francisco. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by Daniel Reich, his nephew and only survivor.

By the time “The Greening of America” was published in 1970, Mr. Reich (the “ch” is pronounced “sh”), a son of privilege and private schools, was already an eminent legal scholar, if something of a heretic. He was best known then for his article “The New Property” (1964), which defended an individual’s right to privacy and autonomy against government prerogative.

That article was cited in 1970 in a landmark United States Supreme Court decision, which broadened the definition of property rights to include licenses, contracts and welfare benefits.

That same year, as the rebellious fervor of the 1960s appeared to be peaking, The New Yorker published a 39,000-word excerpt from “The Greening of America,” giving flower children a powerful intellectual rationale and their worried parents a measure of comfort by casting the younger generation’s values, built on personal happiness instead of material success, as constructive and benign.

The excerpt, and the subsequent best-selling book, gave Mr. Reich a kind of rock-star celebrity. “The Greening of America” entered the canon of sociological megahits published in 1970, alongside Alvin Toffler’s “Future Shock” and Philip Slater’s “The Pursuit of Loneliness.” But while Mr. Reich’s fame spilled beyond the Yale campus, even spawning a character based on him in the comic strip “Doonesbury,” many critics saw his sermonizing as naïve and sentimental.

The New Yorker excerpt portentously began: “There is a revolution underway — not like revolutions of the past. This is the revolution of a new generation. It has originated with the individual and with culture, and if it succeeds it will change the political structure only as its final act.”

Mr. Reich traced the metamorphosis of American society through three levels of consciousness: Consciousness I, the nation’s early self-reliance; Consciousness II, the conformism of the New Deal era; and Consciousness III, an unshackling from the stifling moral constraints of the 1950s, focusing on spiritual fulfillment.

“The extraordinary thing about this new consciousness,” he wrote, “is that it has emerged from the machine-made environment of the corporate state, like flowers pushing up through a concrete pavement.”

He added, “For those who thought the world was irretrievably encased in metal and plastic and sterile stone, it seems a veritable greening of America.”

Charles Alan Reich was born on May 20, 1928, in Manhattan to Dr. Carl and Eleanor (Lesinsky) Reich. His father was a hematologist — Mr. Reich later said that he had learned his father’s diagnostic techniques and applied them to the law — and his mother was a school administrator. The parents later divorced.

Charles and his brother, Peter, attended City and Country School in Greenwich Village and the Lincoln School of Teachers College. (Peter died in 2013.)

Although he was born and bred in the city, Mr. Reich craved the outdoors. He hiked 45 of the 46 high peaks of the Adirondacks.

“Rather than complete the set,” Judith Resnik, founding director of the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale, said in an email, “he thought it would be better to imagine what the 46th looked like.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in history at Oberlin College in Ohio and graduating from Yale Law School, he clerked for Justice Hugo L. Black of the United States Supreme Court and worked at two law firms, Cravath, Swaine & Moore in New York and Arnold, Fortes & Porter in Washington, before returning to Yale in 1960 to teach. His students there later included Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham.

The 25th-anniversary edition of “The Greening of America.” The book, one commentator wrote, combined “the rigor of an intellectual and the enthusiasm of a teenager.”

The 25th-anniversary edition of “The Greening of America.” The book, one commentator wrote, combined “the rigor of an intellectual and the enthusiasm of a teenager.”

Early in his tenure as an assistant professor, “Charles was compelled to teach a course in property law, a subject about which he felt almost completely uninformed,” J. Anthony Kline, a friend who is now the senior presiding justice of the California Court of Appeal, recalled.

Mr. Reich reasoned that if a statutory entitlement, like welfare benefits, was considered property, it was entitled to greater legal protection, Justice Kline said, thereby advancing “an unconventional idea in a legally conventional and persuasive way.”

As a result, the Supreme Court ruled in Goldberg v. Kelly in 1970 that welfare recipients suspected of fraud in New York were entitled to an evidentiary hearing before they could be deprived of benefits.

“The Greening of America” was inspired in part by Mr. Reich’s personal encounters in San Francisco during the so-called Summer of Love in 1967. The book, Roger D. Citron wrote in the New York Law School Law Review in 2007, combined “the rigor of an intellectual and the enthusiasm of a teenager.”

It might not have appeared in print if Mr. Reich’s mother, who ran the Horace Mann School for Nursery Years in New York, had not mentioned to a parent at the school that her son’s manuscript was languishing at a publisher. The parent was Lillian Ross, a writer for The New Yorker and paramour of the magazine’s editor, William Shawn.

The book became a best seller in 1970 despite mixed notices. Reviewing it in The Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt proclaimed that in Mr. Reich “youth culture has gotten its very own Norman Vincent Peale,” referring to the author of “The Power of Positive Thinking.” In Mr. Reich’s utopia, he wrote, “we’ll just stop consuming what we don’t need, stop doing meaningless work, stop playing war and ego games.”

In retrospect, the cultural critic Thomas Hine wrote in 2007, “Reich’s mistake was to interpret minor, transient phenomena as bellwethers of permanent, positive change.”

He added: “Bell-bottoms were, he said, a way of expressing personal freedom, the delight and beauty of movement, and a rather comic attitude toward life. He wasn’t wrong about that, but he seemed to think that people would be wearing bell-bottoms forever.”

Mr. Reich left Yale in 1974. “ ‘The Greening of America’ did me in as far as academe was concerned,” he recalled in 2012.

He moved to San Francisco, where he taught at the University of California, Santa Barbara and the University of San Francisco School of Law and published an autobiography, “The Sorcerer of Bolinas Reef” (1976), in which he revealed that he was gay (although he said he was never defined by his sexuality). He returned to Yale Law School from 1991 to 1995 as a visiting professor at the invitation of Guido Calabresi, the dean.

“Most of us in the mid-1960s thought the world was fine and headed in a comfortably liberal and unified direction,” Professor Calabresi said in an email. “Charley saw it differently and walked the halls of the Law School, in effect, saying, ‘Repent, the end is near.’ ”

He added: “Was it completely correct? No; prophets rarely are. Did it see and enlighten what most of us had missed altogether? Absolutely!”

In writing “The Greening of America” and revisiting his premise 25 years later in “Opposing the System,” Mr. Reich said his goal had been “to make people think.”

By that measure, he succeeded.

His vision of a new consciousness was so universally adopted, he said shortly after “Greening” was published, that “everybody now feels they wrote the book.”

Four decades later, he was asked whether the hopefulness he had expressed had faded.

“It could still be reality,” Mr. Reich replied, “but at the moment it’s viewed as something like a fantasy or a dream that people woke up from with a headache.”

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page B12 of the New York edition with the headline: Charles Reich, 91; Embraced Values of Flower Children.