Review: The Game

Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

The Game

Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968

by George Howe Colt

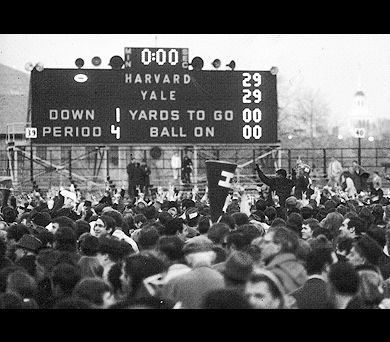

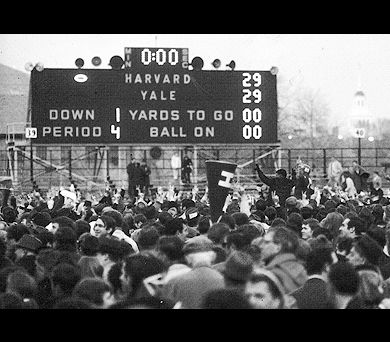

For all of us who saw it, the memory is indelible. Looking left towards the end zone in the gathering darkness. Watching the onside kick recovered with 42 seconds on the clock. The touchdown as time ran out, followed by the two-point play to tie the game, 29 to 29. Sixteen points in three minutes!

For all of us who saw it, the memory is indelible. Looking left towards the end zone in the gathering darkness. Watching the onside kick recovered with 42 seconds on the clock. The touchdown as time ran out, followed by the two-point play to tie the game, 29 to 29. Sixteen points in three minutes!

Well, it was officially a tie, but to every player and spectator on both sides of the Stadium, it was a Harvard victory. After leading comfortably for 57 playing minutes, Yale saw its undefeated season fall apart due to a combination of Yale miscues, bad luck and Harvard brilliance. It’s still hard to believe it really happened; we know (and so did all the Harvard people) that Yale had the better team.

I went to the Harvard game often as an elementary student. We lived in Boston but were a Yale family. At Dexter, the boys’ school I attended, all my classmates’ fathers were Harvard graduates (no one mentioned where, or whether, his mother had gone to college). So I was the odd member of the class, sufficient cause to be bullied at recess. But it never occurred to me to change loyalties. Third Saturday in November of each uneven year I joined my father (Y ’21) on the Harvard Club of Boston’s special train to New Haven (they added a Yale car at the end). Sometimes the trip home was happy; sometimes not.

So on the day of The Game in 1968, I was there, along with my father, my brother Sam (Y ‘56) and my fiancée Jean, who was used to the reciprocal view from her father’s (H ’36) season tickets on the 19 yard line. After the game we pulled ourselves together and went back to her Beacon Hill house for our engagement party. (Our fiftieth anniversary is next March). Everyone at the party agreed it was an afternoon to remember.

George Colt’s book weaves together the high and low political events and social trends of 1968, and their effects on life at both universities, and introduces us to the principal players on both teams, concluding with their post-college lives. Starting with the fall of 1965 when we entered as freshmen, Colt reviews the transformation of both campuses from the coat-and-tie, parietal hours, mandatory physical education (at least at Yale) era to the hell-no-we-won’t-go anti-war demonstrations of 1968 and following years. Yale and Harvard broadened their admissions efforts, although the prep-school/high school ratios remained far more ‘St. Grottlesex’ than the nation’s colleges as a whole.

The narrative of The Game flows like a shoelace, moving back and forth from Cambridge to New Haven and progressing from freshman football in the fall of 1965 to the 1968 game itself. Along the way we meet some of the standout players on both teams and learn their back-stories. Dowling, Hill and Champi of course, but also many of those less covered in the sports pages, including a Harvard player who started on the freshman team in 1963, where his Yale game was interrupted by news of JFK in Dallas (next day’s varsity contest was postponed for a week), then dropped out to join the Marines and serve in Vietnam, returning to Harvard to rejoin the team and play in the 1968 game.

The players’ biographies show us that both teams heavily recruited their players from towns and schools where an Ivy League education was definitely not conventional: working class New England cities and parts of America which we now think of as Trump country.

In between the biographies Colt reviews the football seasons at both colleges in 1965 to 1967, and then each team’s 1968 season game by game, leading to the showdown in the Stadium. For the game itself, the narrative is almost a complete play-by-play, with a whole chapter entitled 42 Seconds, in which each play is recalled from the perspective of several players and spectators. I read through it (taking a lot longer to read than it did to watch) half-hoping for a better ending.

Colt concludes with a section on the 1969 protests at both schools, especially the more dramatic events at Harvard, which involved building occupations, the forceful police response and campus-wide strike. But to both Harvard and Yale these events were a relative hiccup. Graduations took place.

The student movements at both Yale and Harvard wanted to change both institutions radically, but this didn’t happen. Student lives are transient; the universities have centuries of tradition and decades of administration and faculty persistence to resist sudden and permanent changes. The protesters of the sixties wanted to transform the whole country, but this didn’t happen either; Nixon won 49 states in 1972. Most of the football players went on to conventional lives (four did serve in Vietnam; others were 4-F from football injuries).

The Game is worth reading, it will tell you a lot of details you didn’t know about a time we all remember well, fondly or not, and from it we may reflect on what might have, and didn’t, happen as a result.

I just finished the book (a Christmas present from my wife). The description of the game is as painful as my memory of the event. Lots of biographical information I didn’t know. A good read for those of us who lived through it.

Read every word, highly recommend the book for its account of changes and issues at both schools.